Fomaco injectors from Reiser are used for marinating, curing and tenderizing applications in the poultry industry as well as meat and seafood. Source: Reiser.

Poultry processors are up against it. Today, they face issues with water availability, wastewater treatment costs, increasing energy prices, worker safety, food safety and supply chain demands. Grain and commodity prices are up, retailers demand even higher quality, and the industry seems glutted with product. In addition to these challenges, being “green” and maintaining a good public image determine how well a brand is perceived by consumers.

In this further processing application, Heat and Control’s CEIA THS 21 metal detector checks for both magnetic and non-magnetic metals, and continuously tests and recalibrates to maintain maximum stability and performance. Source: Heat and Control.

Not in my backyard!

This month, Sanderson Farms opens its new plant in Kinston, NC, initially employing about 400 people, and increasing to 1,500 when it’s in full operation, according to Mike Cockrell, treasurer and chief financial officer. The project has been warmly received, and according to townspeople interviewed by local news sources, Sanderson Farms is a good corporate citizen and doesn’t cut corners to be a responsible environmental steward.Sanderson Farms had been considering building a second North Carolina location near Wilson, NC. While neighboring Nash County was strongly receptive of a new facility, Wilson was not. Water and environmental concerns, which involved locating wastewater spray fields within a North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources (NCDENR) protected area, nixed the site location. Cockrell says the North Carolina Rural Economic Development Center and Sanderson are looking at other potential sites in Nash County that will be compatible with the environment.

What compounds environmental issues for poultry producers/processors are combined pollution sources-dealing with the manure while growing the birds on the farm, and handling the wastewater and offal when processing the birds. In early 2010, eleven Arkansas poultry companies were put on trial for giving millions of tons of chicken litter to local crop farmers for use as fertilizer which allegedly harmed the Illinois watershed shared by Oklahoma and Arkansas as well as Lake Tenkiller, according to an AP report. Besides being rich in nitrogen, chicken litter contains large amounts of phosphorous, which can pollute a watershed when runoff occurs.

Perdue remedied the problem of excess chicken litter by building a recycling plant. Called AgriRecycle, the $13 million facility processes surplus poultry litter from Delmarva farms into pasteurized, organic fertilizer products. The company provides free poultry house cleanouts to farm partners with more litter than they can use. The finished product meets the Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI) certified organic fertilizer specification and the requirements of USDA’s National Organic Program. It’s used in horticulture, landscaping, organic crop rotation and popular lawn-and-garden products.

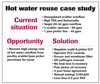

In this hot water reuse case study, overflows from scalder and paw picker lines can be recycled, resulting in an annual savings of more than $180,000. Source: American Water Purification Inc.

Water: The new oil?

A few months ago, a Newsweek feature story on water shortages around the globe and in the US suggested that in the future, water may become as valuable as petroleum in certain regions. Not all poultry processors are faced with a shortage of water, but indeed, the cost of wastewater disposal containing high biological oxygen demand (BOD) loads and total suspended solids (TSS) keeps on climbing. Most processors with large facilities have on-site wastewater processing systems to process the water for certain reuse applications and make it clean enough to send to the public water treatment system without incurring fines.If you ever processed a live chicken for dinner, you know the process uses a lot of water and energy to heat the water for scalding and picking, followed by endless rinsing and chilling. It’s not difficult to accept governmental statistics, that in the 1990s, showed on average it took 8 to 17 gallons of water to process a single 4-5 lb. broiler. But both processing equipment suppliers and processors have improved water consumption over the years since. Last year, NCDENR reported average water usage to process a broiler of the same weight at 3.5 to 10 gallons, which makes a big difference when the scale of birds processed is millions per month.

In 1999, the North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service estimated for an average of 9 gallons of water used per broiler, the total cost of water and sewer service for chicken processors averaged 3.5¢ per bird, ranging from 1.9¢ to a high of 8.6¢ per chicken. Certainly, costs are higher today.

NCDENR offers suggestions to help processors cut water usage and still be within the law during certain stages of processing such as scalding and rinsing, which require continual water replacement. These include:

• Use high-pressure, restricted flow hoses with automatic shutoffs to prevent water loss during inactivity;

• Move dry materials (such as flour) off floors mechanically with vacuum rather than with water;

• Use conveyors to move scrap meat and viscera; and

• Recondition chiller overflow water through filtration, ultraviolet radiation and other accepted techniques; USDA requires an overflow of 0.5 gallon per bird.1

Another way of reducing water usage is through the use of air chilling rather than water chilling, which has been used more in Europe and Canada than in the US. For more information, see “Poultry processors uncover new ways to reduce costs,”Food Engineering, January 2009.

Getting a handle on water usage

Processors must have a plan in place to monitor water usage. “Wayne Farms is constantly looking for ways to conserve water consumption and improve water recycling,” says John Flood, general manager and vice president of Wayne Farms’ further processing business unit. “We track the usage of water (production basis) at our processing plants and compare our performance to the industry via AgriStats.” Beyond saving water, Flood is always looking for investments in “energy-creating opportunities,” as he calls them. “For example, we are presently considering a wastewater methane-gas collection process, which can reduce the amount of purchased fossil fuels in the production steam boilers at one of our slaughter production plants.”A large broiler processing plant that handles 250,000 birds per day and pays $2.50 per 1,000 gallons has the opportunity to reduce water cost by $160,000 annually for each gallon per bird reduction in water use. Some processors report water use of less than 3.5 gallons per bird, which reflects water conservation is working. If, however, a processor uses in excess of 5 gallons per bird, it might be time to hire a knowledgeable consultant who can take a closer look at the operation.2

“Additional water and energy savings can be realized with advanced water treatment technologies, [especially in] chiller and scalder applications,” says Dan Gates, CEO of American Water Purification Inc. (AWPI). Poultry evisceration water reuse is another area for potential savings. Typically, screen and chlorination processes are used, and citric acid additives are often used in the chiller, adds Gates. Chiller overflow water recovery systems can be installed with on-site ozone generators. Ozone is generally more effective with bacteria (99.9 percent kill rate) than chlorine, and both FDA and USDA consider it GRAS for food contact; AWPI has been using ozone since 1997. Since Russia has banned the use of chlorine on poultry imports, ozone is a safe alternative, which leaves no residual levels in product as it breaks down into free oxygen after use.

Recovering hot water from the scalder and paw picker overflows is another way to save energy, says Gates. There’s no rocket science to such a system, just a recombination of existing technologies that can help producers reduce water and energy costs. System components can be simple:

1. A 0.01 micron ceramic filter system removes total TSS from used scalder water, returning it to the hot water system at 85-95 percent clarity (automated controls handle back flushes when needed).

2. An ultraviolet (UV) antimicrobial treatment kills Salmonella, E. coli, Campylobacter and other pathogens, sanitizing the water to USDA standards. The process doesn’t change pH.

3. Heat energy is recovered in the overflows, returning water to the front end at a usable temperature. Water temperature is automatically regulated for defeathering, and all system trends and events can be recorded for quality assurance and traceability.

Systemic ways to save energy related to water

While this article so far has focused on defeathering, washing and chilling operations, there are other places to check, too, says James Rauh, Garratt-Callahan Company cooling water product manager. These include water-saving opportunities in the plant utility room for boiler and cooling tower operations as well as waste treatment options. “And proper boiler firing and use of heat recovery equipment can add to potential energy savings,” states Rauh.Some areas that often waste money include leaking pipes and steam traps resulting in loss of water and BTUs of heat energy, says Rauh. Leaks in condensate return systems also waste water and BTUs. Another common problem is improper burner settings that waste fuel and increases energy costs. Improper chemical feed and residual maintenance cause deposits to form which retard heat transfer and result in increased fuel usage in boilers and electrical consumption in compressors and chillers, adds Rauh.

Operating cooling equipment below maximum achievable cycles of concentration wastes water, BTUs and chemicals. Failure to perform general housekeeping on cooling towers or evaporative condensers can increase fan motor electrical costs. Accumulations of sludge in the basins and plugging of fill material can foul heat transfer surfaces. Lack of a properly applied and maintained microbial control program in cooling equipment can lead to loss of heat transfer with increased electrical costs and potential for equipment damage, says Rauh.

Failure to maintain chemical feed and control equipment can result in corrosion or severe fouling of equipment, both of which consume extra energy and eventually may result in production shutdown for cleaning, repair and possibly replacement. And finally, if on-site waste treatment equipment is not operated and treated properly, potentially recoverable water is lost along with opportunities for recycling that wastewater for reuse in the facility.

Rauh suggests plant audits by an independent water treatment consulting company will help processors save water, energy and money by identifying issues and problems that need to be resolved. A summary water and energy audit will demonstrate potential savings and calculate the ROI that can be achieved.

Avoiding recalls

Compared to the US beef and pork industries, the poultry-meat industry fared very well for the first three-quarters of 2010 on the USDA/FSIS recall archive for pathogens. The same is true for FSIS current recalls and alerts list. The archive contains one turkey breast recall at 17.5 lbs. for Listeria; the current list contains two products for Salmonella and one for Listeria. Of the recalls logged (archived and current), several include foreign materials and a few mislabeled products.When it comes to pathogens, poultry-meat processors are very diligent, or the recall numbers wouldn’t be so low. “Since a large portion of our business is further processed products (marinated, grill marked, cooked/par fired, custom processes/portion control, etc.), we have validated processes and procedures that are science-based to ensure the safety of the products we produce,” says Wayne Farms’ Flood. Flood’s vertically integrated, “farm-to-fork” approach to production and a very linear, well-defined supply chain help determine and eliminate issues-if any-before they get to the level of recall.

Flood is always looking for new and improved process equipment to achieve better throughput, but two other needs are equally important. The equipment must be mechanically easy to maintain, and it must be easy to clean for food safety reasons.

Bacteria can't hide

According to Doug Kozenski, Heat and Control sales manager for prepared foods processing systems, “Heat and Control follows AMI Guidelines for sanitation and construction of ovens and fryers. These guidelines further enhance the cleanable design we have for equipment.” The supplier employs full clean-in-place (CIP) systems to ensure all surfaces of the product zone are thoroughly cleaned during the sanitation cycle. If there are any hard-to-access points, these areas will have specially designed or strategically located CIP spray nozzles to ensure they are fully cleaned, according to Kozenski.A couple of summers ago, Maple Leaf Foods of Ontario, Canada had a serious Listeria contamination, resulting in several recalls and a number of deaths. The cause of the contamination was traced to bacteria build-up in a hard-to-reach area of a slicing machine where cleaning was ineffective.

“Equipment is being designed with fewer places that can trap debris that leads to bacteria growth,” says Dane Woods, Cantrell general manager sales/service/engineering. “Also, technology such as electro-polishing is being widely used to inhibit bacteria growth.” Woods says that as a machine builder, his company is seeing more and more chemical companies introducing antimicrobial agents that kill bacteria and lower the pH to introduce a harsh environment for growth. For more information on antimicrobials and equipment integration, see this month’s Tech Update on pages 123-136.

Heat and Control’s batter and breading applicators are designed with large clean-out openings. All covers open fully but remain on the machine to prevent damage or loss. Platforms for weighers and conveyors are also built to AMI guidelines, and the framework is constructed to eliminate flat surfaces where debris and moisture can accumulate. Supports raise equipment above the deck surface to facilitate cleaning. According to Kozenski, conveyors are also designed for easy cleaning access, and side guides and covers on incline conveyors pivot open for full cleaning access. The supplier’s FastBack horizontal motion conveyors now feature sloped plastic covers that shed water and seamless pans with large radius corners.

“If you look at the design of equipment today versus just five years ago, food safety has been a high-priority consideration,” says Jeff Ray, marketing manager of Marel Food Systems. Equipment design should be simplified wherever possible. For example, there should be no exposed pulleys, gears or belts. For processing equipment like slicers, the use of direct-drive, enclosed stainless steel (SS) motors makes sense, eliminating several places for bacteria to hide and multiply, adds Ray. The use of variable frequency drives and fully automated controls can both save energy and make equipment safer for operators.

Applying the same principles to conveyors may not necessarily eliminate the moving belt as a horizontal motion conveyor does, but for belted conveyors, Ray says using direct-drive SS pulley motors solves several cleanliness issues at once. There are no drive belts or chains between the motor and the belt, and with completely sealed pulley motors, the gearing is internal and protected from washdowns, and provides no place for bacteria to multiply.

According to Dan Plante, JBT FoodTech North American sales director, choosing high-end, sophisticated SS alloys in building machines provides better thermal and corrosion-resistant properties while making components easier to clean. Conveyor belting is also an important issue in the fight against bacteria. Plante says belts need to work closely with drive mechanisms, freezers and ovens, and the use of shelf-stacking belts makes this integration easier to do.

Foreign materials/bones

If you add up the entries in FSIS logs, foreign materials (FM) accounted for as many or more recalls in the poultry industry than bacterial contamination. “Metal detection continues to be the standard for contaminant detection in most poultry plants,” says Kevin Jesch, Heat and Control inspection systems product manager. Metal detectors should be able to filter out the product effect for fresh or frozen applications.As with all processing equipment in a poultry plant, metal detector systems should be rated IP69K, which is a high-pressure/high-temperature washdown rating, says Jesch. Any level of water intrusion can result in corrosion of electronic circuit boards, which can impair operation.

A perennial problem for inspection systems is being able to spot bones and cartilage. Beyond the capability of a metal detector, detecting these materials-which are often very soft in a young broiler-can be challenging even for X-ray systems, according to Ray. “We had one processor where we literally found 50,000 bones in one year in its chicken breast line,” he says. He had to build a complete recovery and rework system to solve this problem. Now, when an on-line SensorX X-ray system spots a chicken breast with a remaining bone fragment, the breast is kicked out and sent to a rework operator, along with the electronic image showing where the bone is. The operator finds the bone based on the image, removes it, then throws the breast back on the line, and it is again checked to make sure the operator completely removed the bone, explains Ray.

Larger chickens, bigger problems

Chickens entering the processing plant have been gradually getting a little bigger for their age. While this may be good from a yield standpoint, it has created new issues. “Larger bird sizes are driving processors to look at different ways to cut products,” says Jan Gaydos, JBT FoodTech North American marketing director. “We have added capabilities to our portfolio in ways that allow us to give processors the tools they need to utilize bigger raw material.”As more consumers want fully cooked or RTE chicken, the demand for boneless is becoming greater, and that means processors need deboning operations and X-ray systems, says Ray.

“I really don’t see many bone-in chicken applications. The 8- or 9-piece pack used to be popular,” says Plante, “but then more people want fully cooked chicken and that’s where the trend continues to go.

“Many processors have returned to deboning by humans, because of the variability on birds,” adds Plante. “Because of this, we have gone back to our equipment design to help processors deal with breasts that are bigger. That is where our DSI slicer comes in-because it is able to deal with larger birds, and also keeps workers safe.”

Worker safety is critical in equipment design and function, says Woods. Automatic deboners require precision, regular maintenance, new parts and upkeep that some processors are not willing to spend the money to support. “Manual deboning still is hard to beat for yields,” concludes Woods.

Automation can help save energy, improve product

While some in the industry may have concluded automatic deboning machines can’t cut it, there are other places automation can help-producing a consistent product, saving energy and managing the supply chain. “We have automated our ovens and fryers to a large extent,” says Kozenski. “When using PLC/PC controls, we automatically control all cook parameters of the oven and/or fryer.” While the cook parameters are not automatically adjusted on the fly based on automated input, they are repeatable through the use of saved recipes, and can be manually adjusted during production, he adds.The perennial problem of the industry-how to check internal doneness is not just an issue with hamburgers. Cooking parameters would ideally be based on product temperature or yield as product exits the oven or fryer, says Kozenski. “Unfortunately there are no reliable methods with which to monitor internal [core] temps or the net yields on the fly.

“Recently, we introduced a new manufacturing information platform called Information That Matters,” says Kozenski. It collects KPIs from critical control points in the line and sends them in real time to smart phones and computers. The system helps measure overall equipment effectiveness (OEE) and informs operators and maintenance people of faults and adjustment needs.

Suppliers also need to be attentive to new designs that can save energy. Plante says JBT FoodTech has updated designs that reduce water consumption and power usage. One example he cites is an LVS feed system with coils that saves money in power consumption.

Supply chain unknowns

Supply chain issues are hitting processors from every angle. Wayne Farms’ Flood lists a few cost concerns: commodities (grain/feed), labor, competition, amount of product in the marketplace, transportation, etc.According to USDA’s “Chicken and Egg” report, broiler chicks hatched during October 2010 totaled 767 million, up 5 percent from October 2009. Eggs in incubators totaled 618 million on November 1, 2010, up 7 percent from a year earlier. The question that might be asked is: When the market seems already glutted with product and with higher feed costs, why would the industry increase the flock, eroding profit margins?

With the passage of the Food Safety Modernization Act, S. 510, giving the FDA more power, how will this play out in industries monitored by USDA? It remains to be seen. “The bill’s requirements for surveillance and traceability will task the FDA with establishing a tracing system for both unprocessed and processed food, increasing our ability to quickly detect potential problems and determine quick, life-saving solutions,” says Brian Cute, vice president of Afilias Discovery Services. “Importantly, interoperable and standards-based traceability services will provide cost-effective solutions for farmers, food producers, processors and retailers alike.”

While technology has solved several problems, suppliers should not lose sight of what poultry processors need today-strategic relationships!

“We obviously want equipment that is reliable, durable and has a significant life and associated warranties,” says Wayne Farms’ Flood, “but we also want our equipment suppliers to have longevity. We prefer our vendors to be strategic partners who will support us in continuous improvement initiatives. Our suppliers need to actively and continuously research new technologies to better engineer their equipment and increase its efficiency.”

References:

1Saravia, et al. (2005). “Economic Analysis of Recycling Chiller Water in Poultry-Processing Plants Using Ultrafiltration Membrane Systems,” Journal of Food Distribution Research, pp 161-166.

For more information:

Dan Gates, American Water Purification, Inc., 316-685-3333 (ext. 104), dgates@awpi.biz

James Rauh, Garratt-Callahan Company, 650-697-5811, jrauh@g-c.com

Doug Kozenski, Heat and Control, 847-226-5392, dougk@heatandcontrol.com

Jeff Ray, Marel Food Systems, 913-888-9110, jeff.ray@marel.com

Dan Plante, JBT FoodTech, 419-626-0304, daniel.plante@jbtc.com

Jan Gaydos, JBT FoodTech, 419-626-0304, jan.gaydos@jbtc.com

Dane Woods, Cantrell, 770-536-3611, dwoods@cantrell.com

Kevin Jesch, Heat and Control, 510-259-0500, kevinj@heatandcontrol.com

Brian Cute, Afilias, 215-706-5700, briancute@afilias.info