Food Safety

How food processors can create a plan for traceability and recalls

All processors need a program for traceability and recalls

As processors adopt more flexible solutions for tracking ingredients and products throughout their entire production cycles, handheld devices and other digital tools help manage inventory and supply chain tracking.

Photo courtesy of Getty Images

Processors use a range of schemes to track products and raw ingredients, with blockchain getting more attention as a potential record- keeping method.

Photo courtesy of Getty Images

The ability to track fresh produce from its origins can help make recalls more efficient and stop outbreaks before they spread.

Photo courtesy of Getty Images

All food processors, no matter what they produce or where they are located, should develop, document, implement and maintain a program for traceability and recalls.

Why? There are occasional quality issues that require removing products from distribution. A strong plan is simply a good business practice. It’s also a means for potentially protecting public health.

One of the required preventive controls for food processors under the “Current Good Manufacturing Practice, Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food” regulation found in 21 CFR Part 117 is a mandate to have a recall program if your products and processes include hazards requiring a preventive control.

There are people in the industry who seem to believe that the mandates for establishing programs for traceability and recalls are fairly new, but that is not the case. The low-acid canned food regulations found in 21 CFR Part 113 have required that processors of such products be able to do this for almost 50 years, as may be seen in 21 CFR Part 113.100: “Records shall be maintained to identify the initial distribution of the finished product to facilitate, when necessary, the segregation of specific food lots that may have become contaminated or otherwise rendered unfit for their intended use.”

This simple statement implies that finished products must be clearly identified so that they can be traced in the event there is a problem.

The seafood HACCP regulation that was finalized in 1995 created the concept of prerequisite programs and served as a benchmark for streamlining HACCP plans. Two of the basic prerequisite concepts addressed in the regulation were product identification and traceability and recalls. So, again, we see a regulatory mandate for being able to trace and recall products. Even though product identification—which includes identification of ingredients, raw materials and packaging—and traceability and recalls are addressed separately, they go hand in hand. Without properly identifying materials or finished goods, tracing them is impossible.

The bottom line is that food processors have a mandate to establish programs for product identification, traceability and recall. This is reinforced through third-party audit schemes, such as those established through the Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI) and private schemes developed by firms such as the American Institute of Baking (AIB) and NSF. The importance of programs for recall and traceability is further underscored when one looks at trade association websites. Most of these organizations have developed guidance documents or other resources to assist their member companies in establishing recall and traceability programs.

Necessary elements

Programs for traceability and recall include many different elements. Ideally, the program should be developed, documented, implemented and maintained by a team, often called the Recall Action Team. Some companies utilize a pair of teams, a working team and a decision team. These should be multidisciplinary teams. The working team might consist of persons from the following groups:

- Recall team leader

- Recall core team

- Legal/regulatory

- Public relations

- Consumer affairs

- Production/operations

- Quality/food safety

- Distribution/logistics

- Marketing/sales

The decision team might include:

- Senior management and president/CEO

- Chief in-house or outside counsel

- Chief scientific officer

The company must develop and document procedures for people or groups making up the recall team or teams. They must then not only be trained on the protocols, but also must practice them so they understand what to do if there is a problem. In addition, it is a good idea to ensure that each person making up the recall team has a backup, who is also fully up to speed. When there is a problem, it must be all hands on deck. Confusion has been a significant issue when processors have had to implement recalls. People simply did not understand their roles in the process and ended up making a bad situation worse.

Processors must also establish a program to ensure employees know what to do in the event of a recall. If the 6 p.m. news truck pulls up in front of your plant following a recall announcement, the last thing a company wants is to have the media interviewing line workers. So, part of the orientation and training for all workers would be explaining their role in a recall, which is to simply not talk about it to anyone: media, friends or even family.

This leads to what are considered the three legs of a traceability and recall program: technical, legal and communication. The procedures that a company develops, documents and implements must take all these elements into consideration. Communication was the last of the legs to be added as people realized that it was absolutely essential to ensuring a functioning recall program.

So, what elements should be included in a traceability and recall program? More than some might think, including programs in many different departments, such as receiving, shipping, warehousing, production, quality, logistics and purchasing. Elements would include but need not be limited to:

- Establishing tracking procedures for raw materials, ingredients and packaging materials

- Ensuring that suppliers can trace raw materials, especially fresh produce to the fields in which it was grown

- Properly documenting lots of raw materials, ingredients and packaging used in production

- Establishing procedures for rework that ensure any materials that are reworked are properly documented and traceable

- Establishing procedures for properly coding all finished products

- Establishing procedures to ensure that production has accurate inventories of all finished goods

- Ensuring products are properly stored in the warehouse and that warehouse workers pick the proper lots for shipping

- Verifying at the loading dock that products picked for shipment match the bills of lading

- Establishing procedures that clearly document which lots are being shipped where

- Establishing systems to track product that has been shipped

- Developing procedures for all members of the recall team to follow

- Establishing procedures for training all recall team members and backups and documenting that training

- Establishing procedures for conducting mock recalls

- Establishing a procedure for reviewing all mock recalls and real recall issues, as part of a continual improvement program

- Establishing procedures to remove product from store shelves, a great challenge for large companies

Let’s take a look at some of these elements. The first point, establishing tracking procedures for raw materials, ingredients and packaging materials, sets the tone for a company’s ability to properly document what is used in production and from where it came.

Processors utilize a range of tracking schemes. The easiest option is to simply use the lot code from the supplier throughout the process. This has advantages and disadvantages in that lot numbers might be misread or hard to read.

Other operations establish a unique lot code for each material as it is received. The company then identifies the supplier lot in the system using a unique code. This entails a bit more work, because the incoming materials must now be tagged with the company code. One benefit to this procedure is that the new lots can be bar coded, which allows easier tracing. This does, however, add cost.

The second point addresses purchasing of fresh produce. It is up to the purchasing group and quality assurance or an agricultural group to work with raw produce suppliers to ensure that their programs allow traceability back to the fields. The recent romaine lettuce outbreak further underscores the importance.

Production must develop and implement procedures to properly document the lots of raw materials, ingredients and packaging used during production. Perhaps the greatest challenge when developing this traceability program is handling changes in lots during production. It is up to the production people to properly document what is actually being used, not what they assume is there. This is an area where the bar coding can pay off. Some companies apply additional bar codes to raw materials or ingredients that can be peeled off the material and applied to the production records.

One challenge that some processors, especially small ones, must address is shipping products less than load, or LTL. This involves small loads, which oftentimes include mixed pallets. With more and more products ordered online, food processors that ship gift packs and other items are still obligated to ensure that those items are properly identified and traceable in the event of a problem.

Mock recalls are an essential element in a company’s traceability and recall program. Almost all third-party audits require one or two recall exercises, both back and forward traces. Companies need to establish procedures that include targets, usually 100 percent or higher recovery within two to four hours.

When developing a mock recall program, it should be more than just a trace of the finished goods or raw materials. It is a test of the whole team. Each and every member of the recall action team should be involved, gathering whatever information the documented procedures call for. This is what must be done if there is a real-life recall, so get the practice in. The recall program should also include a review of each recall exercise, both mock and real, by the recall action team.

Lastly, it is imperative that companies develop procedures to make sure that all product involved in a recall is accounted for and either brought back or destroyed. This can be a huge challenge for major producers. As an example, when Conagra conducted a peanut butter recall back in 2007, the company had to get product out of some 50,000 stores. A 2017 recall initiated by Newly Weds Foods was even larger, including over 100 products in retail outlets and foodservice and 90,000 locations.

The process is somewhat easier for suppliers of food packaging, ingredients and raw materials, but there is also the issue of what to do with foods already manufactured using the suspect item. This is what contributed to the downfall of the Peanut Corporation of America. Its suspect items went into many other products, forcing customers to conduct recalls, which were charged back to the company.

For businesses producing retail items, working with a company like RQA Inc. can help address the challenge of getting items off retail shelves. RQA uses a network of agents throughout the country to remove products.

“Planning and execution are the keys to a successful recall,” RQA President Larry Platt says.

RQA has provided product recall and recovery services to manufacturers and retailers since 1989. “Ideally, our relationships with clients begin with planning and practice.”

RQA evaluates recall plans, not only for regulatory compliance, but also for clarity, completeness and inclusion of industry best practices. Then, pre-incident work includes recall simulations based on customized, real-life scenarios that escalate and challenge the team’s knowledge of corporate procedure, data gathering and decision-making processes.

When the time comes to execute a recall, RQA can deploy its nationwide field force of over 3,500 people in North America alone to remove affected product from retail stores and the entire supply chain. Finally, RQA will manage final product disposition, whether rework or disposal in landfills or via incineration.

Enhancing your recall program

There are many different tools and strategies that can be used to enhance a company’s ability to conduct a recall. Companies use different software programs for traceability or adapt other technologies. SAP’s software is something that most people associate with inventory management, but it used by some for traceability. One technology being looked at is blockchain.

According to a publication of the IFT Global Food Traceability Center (2017), “The term blockchain was first used by Satoshi Nakamoto, a pseudonymous person or entity, in a 2008 paper conceptualizing chronological blocks of data linked through a networked cryptologic chain. The following year, Nakamoto created bitcoin based on this concept. Although the initial iteration of blockchain technologies concentrated on creating noninstitutional currency, the technology is essentially a ledger with a wide potential of features, depending on the architecture.” Areas in the food industry where this might be adopted include finance, logistics and traceability.

There are food processors that are looking closely at blockchain technology and others that have initiated trials. One of these companies is Golden State Foods, a major supplier to McDonald’s and others. The key to blockchain is that it utilizes hash-based cryptology to ensure security and trust. The IFT Global Food Traceability Center (2017) explains how this works:

“The blockchain has three essential pieces of data: the transaction timestamp, transaction details and a new hash combining the hash and details of the previous transaction. Each transaction is then distributed throughout the network. Through this process, a continuous encrypted record of the transaction is kept and becomes immutable once added to the blockchain.”

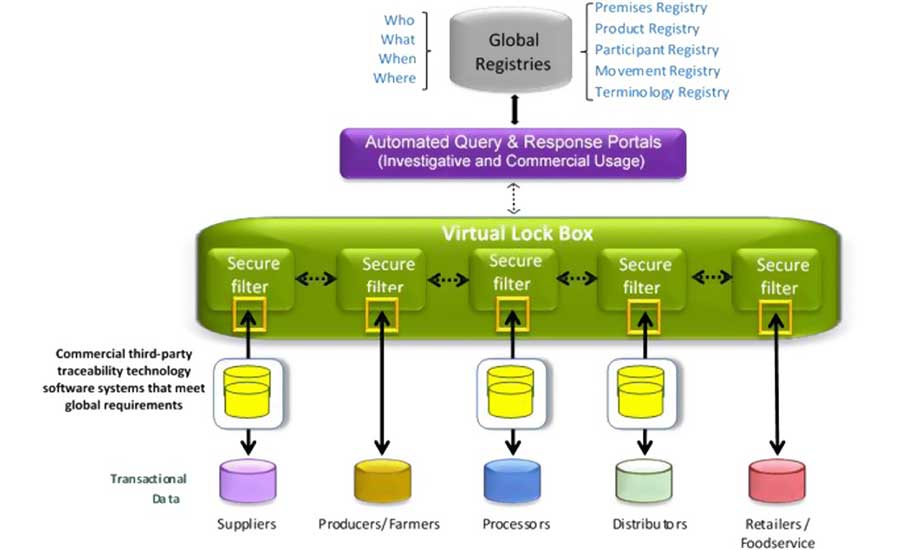

This chart from the Institute of Food Technologists shows how blockchain might work in a supply chain for food traceability. (Click to enlarge.)

Blockchain systems would be more transparent and decentralized, but could allow access to data to different groups in the supply chain. Yet, the system would have the ability to ensure security of data and trade secrets.

As technology grows, there are more and more tools to enhance a company’s traceability and recall programs. Blockchain is one in its infancy, but it has elicited significant interest throughout the food processing industry. There is great potential in its use, but it is not yet the panacea that some believe it is. It is still a baby in the big picture, so let’s see what goes on in the future.

But, blockchain or not, food processors need to build programs for product and ingredient/raw material/packaging traceability that include those 15 elements highlighted earlier. These elements help ensure a solid base may be enhanced through new technologies.

For more information:

RQA Inc., www.rqa-inc.com

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!