Connecting process control, CIP, HVAC and energy management

In many facilities, these systems are manual and standalone, with no coordination—other than human

Boilers today have stack economizers to prevent heat from “going up the chimney.” Instead, it is captured and used for other heating purposes—such as space heating or water pre-heating. Boiler control systems today can monitor and send data to other supervisory controls. Photo courtesy of Bill Nichols

As energy becomes more costly and product quality and food safety increasingly critical, integrating energy management, clean-in-place (CIP), process and environmental controls is becoming more practical and economical as digital controls provide the linking together of these systems—if not directly, then by making them available on the same device for operators and managers.

This article looks at the potential benefits of integrating energy management, process control and HVAC systems into a loosely or tightly coupled plant-wide system that improves product quality and saves energy as well. It provides some practical pointers on integrating these systems and what food or beverage facilities can expect from this linking together of systems.

To get neutral opinions on the subject, I spoke with engineering houses and A&E firms who are often the people that have to make all these disparate systems function together, and even if not digitally connected, they still have to be easily coordinated by facility operators.

For example, Gray Solutions, a Gray Company, has had the call to integrate building management systems (BMS) outputs into process controls to allow for real-time trending and reporting of building/utility systems in addition to production data.

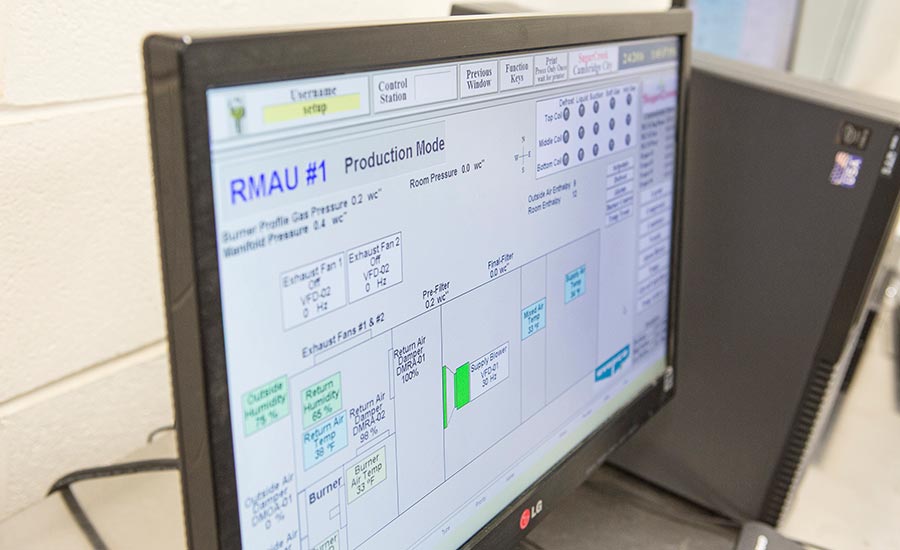

HVAC controls screen can be pulled up anywhere within the plant, making it easy for operators to check room pressures and temperatures plus take a look at burner controls. Photo courtesy of Ross Van Pelt, RVP Photography

HVAC controls screen can be pulled up anywhere within the plant, making it easy for operators to check room pressures and temperatures plus take a look at burner controls. Photo courtesy of Ross Van Pelt, RVP Photography

CRB has implemented energy metering with respect to providing the physical meters for electrical power consumption, natural gas consumption, water consumption, waste output, and mechanical and process utility system monitoring such as steam, chilled water/chilled glycol and heating hot water/hot glycol usage.

Stellar’s engineering teams have experience in integrating systems within a facility or connecting facilities together. As with most engineering houses, they’re pretty system agnostic, so they’re not likely to push any one supplier’s controls equipment—whether for building automation or process controls.

Founded in 1979, Spec Engineering, also a Gray Company, has worked with large food and pet food manufacturers and has experience in integrating all sorts of systems—from processing to HVAC and CIP and material handling systems. This engineering group works with automation from several hardware vendors.

CIP control panel connects to CIP skid to the left and can connect to the plant-wide Ethernet and be integrated into process control and energy management systems to make CIP an integral part of the process. Photo courtesy of Wayne Labs

CIP control panel connects to CIP skid to the left and can connect to the plant-wide Ethernet and be integrated into process control and energy management systems to make CIP an integral part of the process. Photo courtesy of Wayne Labs

CIP automation/integration an important trend today

While there has been some interest in integrating process control systems with HVAC or BMS, the key system of interest in integrating with process controls is CIP. Of course, older production systems may not have CIP, or if they do, CIP may be manually operated, which means operators need to remember to switch a lot of specific valves in the right sequence. Today, smart mix-proof valves under the direction of the process control and/or CIP system can make the change between process and cleaning mode in a matter of seconds—with no error.

CIP is great for speed and efficiency, but the drawback is that the process line is down for the time period CIP is in use, says Andrew David Hager, BSME, PE, LEED-AP, CRB senior mechanical engineer. This may be fine for some processors who have the ability to take a process line down. For other processors with 24 hour operations, to implement CIP will require a second process line for redundancy or possibly a reduction in product output even with multiple lines in operation.

The interest in employing CIP integration has been around for some time, but knowing how to integrate the information into control sequences and measure the results is most important, says Stellar’s Brad Smith, director of business/product development. CIP should be integrated as it can have an impact on facility refrigeration loads and cause false loading of the plant. “You can also improve CIP efficiency by adding waste heat recovery and potable water preheat,” adds Smith.

“CIP systems use three primary utilities that have energy inputs: steam from the boiler, air from the compressor, and electricity from the power distribution system,” says Jonathan Malakoff, subject matter expert liquid systems, Spec Engineering. The air utilized for valve controls and possible line purges is a relatively small capacity user, and electricity to run CIP skid supply pumps is typically a low requirement compared to the remainder of plant equipment.

However, depending upon the other simultaneous users of the plant boiler, the short-term steam requirements to heat quickly large batches of cleaning chemicals and water rinses to high temperatures could spike the demand, says Malakoff. This more frequently occurs in older, smaller boiler units that may have been outgrown and in steam piping systems that have been expanded through time but have undersized or inefficient plant headers and branches. Due to the nature of CIP operations, the CIP schedule may be able to be arranged to occur on second or third shifts at plants when those utilities are less taxed and costly to operate. Accordingly, CIP considerations can have a positive effect on an overall plant energy management program.

In a CIP mode, evaporators are shut down until cleaning is finished. Afterwards, the refrigeration system is restarted. Here is a case where CIP and HVAC controls can be teamed up with the process control system to make this process happen optimally and save energy. Photo courtesy of Ross Van Pelt, RVP Photography

In a CIP mode, evaporators are shut down until cleaning is finished. Afterwards, the refrigeration system is restarted. Here is a case where CIP and HVAC controls can be teamed up with the process control system to make this process happen optimally and save energy. Photo courtesy of Ross Van Pelt, RVP Photography

Tracking down costs

As energy costs continue to increase, food and beverage manufacturers are taking a closer look to control these expenses to gain a critical competitive advantage, says Jeff Jendryk, vice president of business development, Spec Engineering. The key to reducing energy related expenses is to understand where they are coming from and how much is being consumed. With this information manufacturers can proactively manage their requirements, improve systems performance and reduce costs.

“We are currently seeing more customers wanting to know utility usage by major process area or equipment, where before it was more common to see only total site usage—or even only leverage quantities from monthly bills,” says Drew Goodall, director of process, Gray Solutions. Branch meters allow control systems to collect energy utilization at a more detailed level and easily tie this information back to system or equipment-run data. “We can then easily generate instantaneous, daily, weekly, or monthly reports comparing energy usage per unit of production. This is invaluable information to the operations and maintenance teams.”

Refrigeration and process loads typically account for the majority of energy consumption, so having them share dynamic load information makes the most sense, says Stellar’s Smith.

Smart, mix-proof valves with blue covers connect to the process control system, which is integrated with CIP to provide automatic switching between the process and cleaning, preventing operators from making costly mistakes when operating old manual valves. Photo courtesy of Wayne Labs

Smart, mix-proof valves with blue covers connect to the process control system, which is integrated with CIP to provide automatic switching between the process and cleaning, preventing operators from making costly mistakes when operating old manual valves. Photo courtesy of Wayne Labs

Integration and sharing information

While CIP may seem costly to implement, in the long run it can pay for itself. “CIP is a time saver,” says CRB’s Hager. While expensive at first cost, it can provide quick payback with reduced down time and less labor, and can decrease needed resources.

Hager, however, makes an important point: Plant HVAC systems during CIP do not function as they would under normal manufacturing conditions. During cleaning and disinfection, the HVAC systems are turned to full 100% outdoor air to flush the areas with outdoor air as the staff works to clean and disinfect. This requires significant energy for the HVAC system, especially when the cleaning and disinfection process is complete, and the HVAC system has to operate at full capacity to bring the area environment back into a controlled manufacturing environment.

So, what applications can benefit from the integration of CIP, HVAC and environmental systems? Gray Solutions’ Goodall sums it up: Applications with intensive heating, cooling, and other air transfer systems—anywhere an exchange of utility media outside the building envelope is required— as well as any processes with rigorous water and wastewater utilization, benefit from energy management and process control integration. Pet food manufacturing is a great example since it is an energy-intensive process to cook, cool, and, sometimes, freeze large amounts of product in short time periods, and then, clean everything quickly.

Decide if an integration process is practical

If you have older systems, you have to ask if it’s practical to upgrade these systems before you can integrate them—as they will probably need sensors, controllers and associated and I/O equipment. So, how would you do a cost-benefits study to determine ROI?

Some systems are simply so old and obsolete that they should be upgraded regardless, says Stellar’s Smith. However, if the upgrade is based on its ability to be integrated, then it comes down to the amount of equipment connected to the system and how much of an impact that has on overall energy consumption. “Personally, I am not a fan of piecemeal integration since integration can become complex and difficult to maintain for future generations,” says Smith.

Older systems can be integrated or updated to a point with respect to line equipment and HVAC systems, says CRB’s Hager. Integrations will eventually lead to a point of diminishing return, where money spent does not justify the minimal gain that is realized. That’s when it is time for equipment replacement and/or complete line replacement (even new construction) to take advantage of advances made in new technology, materials and practices.

Suppose you want to set up an energy monitoring program, and integrating systems is necessary to accomplish it. Integrating systems, however, goes beyond just equipment; people are involved, too. “The first step is to set a realistic goal,” says Spec Engineering’s Jendryk. “Identify and monitor your processes and equipment, analyze your results and continue to improve. Staff will need to be trained on how to assess potential opportunities and make improvements.” Project scopes will need to be identified, and setting up an execution plan is also a critical step in being successful. In establishing an energy monitoring program, setting up baselines and metrics is important to track results.

Today’s ammonia refrigeration compressors have local screens, but can also communicate via network systems to connect with remote control systems and share data with process controls and HVAC operator workstations. Photo courtesy of Bill Nichols

Today’s ammonia refrigeration compressors have local screens, but can also communicate via network systems to connect with remote control systems and share data with process controls and HVAC operator workstations. Photo courtesy of Bill Nichols

Typical solutions start with developing a commonality document to outline the conventional hardware and software solutions desired to produce the end state, says Gray Solutions’ Goodall. Once a design is completed and priced, certain elements may be removed or shifted to a phased implementation to meet budgetary requirements. Due to the rapid advances in technology, it often does not make sense to integrate an older (i.e., a no longer OEM-supported) system or technology into a new solution. Cost benefit or ROI is typically tied to reallocation of personnel, increased production throughput, or realized energy savings through tighter control/monitoring.

Is integration easier in a greenfield site?

Both new and old facilities can benefit from integration, says Jendryk. Depending on the age of current systems, larger paybacks are often found on older facilities.

Fortunately, integration can be implemented in any facility, new or existing operations, says Goodall. New facilities allow for a one-time startup, where retrofits may be phased to be brought online during routine downtime.

The question of whether integration is more suited to a greenfield site is probably on the minds of facility operators and mangers and corporate production managers constantly, says Hager. “When is the best time to upgrade versus the best time to build new?” It is a day-to-day thought to at least someone in each group. The answer is all about risk and reward: Doing the right thing at the right time and always looking ahead and planning ahead. Innovation will keep improving practices, which in turn drives more innovation. The “need” comes first because we all require a “need” in order to demonstrate a change is required.

While integration is easier when starting from scratch in a greenfield site, more important, as Hager points out, is that management needs to determine its needs and requirements. “If it’s not a design requirement, it likely won’t happen,” says Smith. Specifications will often require various systems to communicate with another vendor’s equipment, but then don’t go far enough in detailing the purpose of the connection. In these situations, the physical connection can be complete without any data exchange. Using the same company for multiple control applications such as process, refrigeration and HVAC can enhance integration and what information is shared.

Who’s best qualified to integrate process, HVAC systems?

While suppliers of process control/automation equipment know their systems well, and HVAC suppliers are also capable, it would seem that a broad range of experience would be needed to tie systems together for smooth data flow and obtaining actionable information. So, are suppliers up to the task, or is it better left to system integrators (SIs)?

“It all depends on the firm’s level of experience,” says Spec Solutions’ Jendryk. HVAC systems are becoming more complex with the need for specialization. As HVAC technology and design continue to become more sophisticated, it is important to make effective use of all the data available. Systems are being designed with lighting, energy metering, HVAC, and other building systems to make effective building management system decisions.

“Consider opportunities to test integrations and gauge return in a smaller-scale environment.”

—Andrew David Hager, senior mechanical engineer, CRB

Gray Solutions’ Goodall suggests that end-to-end integration is typically best served by SIs as they provide a vendor-agnostic solution and should have expertise across many different platforms. However, systems at the unit-operation level may be better served by an OEM provider.

The integration process can be performed by system integrators or suppliers, but they must have the expertise to know what to do with the information, allowing for sequences of operation to incorporate the data, says Stellar’s Smith. This comes down to an individual or team experience involved in a project and project budget.

Integration is best performed by an integrated team—designers working with both suppliers and system integrators, says CRB’s Hager. “Suppliers would be smart to have system integrators on staff and as a service for the controls they sell. Many times, I have used system integrators in design development that also sell the controls, and yes, I have paid them for this service just as I would pay for a sub-contractor service. The integrators do not always win the bid for the controls.”

Many people will say to be “very careful” with system integrators that also sell controls because there is an assumed distrust for something to be missing that only the integrator knew about, says Hager. Set the expectations early and keep attention to the deliverables. It doesn’t hurt anyone to have a third-party review and comment regarding approach, capacity and discipline design.

Start small—work up to larger projects

There’s no need to go hog wild and take on a project that’s so big that it could fail. “Consider opportunities to test integrations and gauge return in a smaller-scale environment,” says Hager. A processor in the Midwest is using the latest advancements on a small scale, tapping equipment manufacturers’ newest equipment and technology. Once proven, the company scales up the operation either in new facilities or by upgrading an existing facility depending upon return on investment.

“We have a lot of experience with integrating waste heat recovered from the refrigeration process into HVAC systems or city water preheat for CIP systems,” says Stellar’s Smith. In this producer-consumer model, the refrigeration system becomes the “producer” of waste heat and the HVAC or CIP systems become the “consumer” of waste heat. Essentially the HVAC system becomes a fluid cooler and saves energy, chemicals and water. By having the HVAC consume waste heat, under certain circumstances it can increase indoor air quality by bringing in more fresh air than would normally be allowed. It also reduces equipment runtime and energy consumption by not operating the condensing system and reduces chemical consumption by reducing water usage.

It requires integration on the mechanical side between the refrigeration and HVAC teams and, in the best situation, a single automation vendor handling the complete control system. “We have worked with both greenfield and retrofit applications for this type of application,” says Smith.

What’s ahead?

As the benefits of integration are better understood by consultants and end users, it will become increasingly common to see such integration requirements spelled out, says Smith. Rising energy costs and a move to more green solutions will eventually demand better integrated solutions.

Jendryk sees major improvements in HVAC technology such that it will focus on sustainability, automation and actionable data.

“Looking ahead, we believe enhanced monitoring of building management systems and utility systems will become part of this process,” says Goodall. Wireless sensors allow for even more data harvesting at branch, point, or remote system locations to allow for real-time monitoring of process and utility data. When coupled with machine learning, control systems can predict energy loss and allow it to be addressed before there is an issue.

The additional data provided from new monitoring systems allows for a system or site gap analysis to be completed more easily and effectively, adds Goodall. This analysis allows engineers to find sub-optimal operating systems or pair waste energy sources with the most sensible user to be harvested or recouped before being lost.

Integration of existing systems will always be part of equation, because at first, upgrades are less expensive than building new plants, says Hager. However, there are limitations to how many upgrades can take place. The future of integration of electro-mechanicals, process controls and plant HVAC systems will be to design the accommodation for upgrades into the design development so manufacturers can extend their ability to upgrade over time. In all things, plan for flexibility and expansion.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!